Development of Life Prediction Models for High Strength Steel in a Hydrogen Emitting Environment

Solvent substitution for maintenance and overhaul operations of military systems has been a primary environmental concern for many years. Cadmium replacement in these systems has been targeted for decades. Both of these areas have a common obstacle for implementation of any potential alternate. Hydrogen embrittlement of high strength steel is the most predominant unforeseen hurdle since high strength materials show sensitivity to the phenomena and the source of the hydrogen can be anything within the fabrication process, maintenance practice or the natural corrosion cycle. Standardized testing on this issue has traditionally stemmed from the aerospace industry where it is a principal focus.

by Scott M. Grendahl, U.S. Army Research Laboratory Aberdeen Proving Ground; and Ed Babcock, Stephen Gaydos and Joseph Osborne, the Boeing Co.

Solvent substitution for maintenance and overhaul operations of military systems has been a primary environmental concern for many years. Cadmium replacement in these systems has been targeted for decades. Both of these areas have a common obstacle for implementation of any potential alternate. Hydrogen embrittlement of high strength steel is the most predominant unforeseen hurdle since high strength materials show sensitivity to the phenomena and the source of the hydrogen can be anything within the fabrication process, maintenance practice or the natural corrosion cycle. Standardized testing on this issue has traditionally stemmed from the aerospace industry where it is a principal focus.

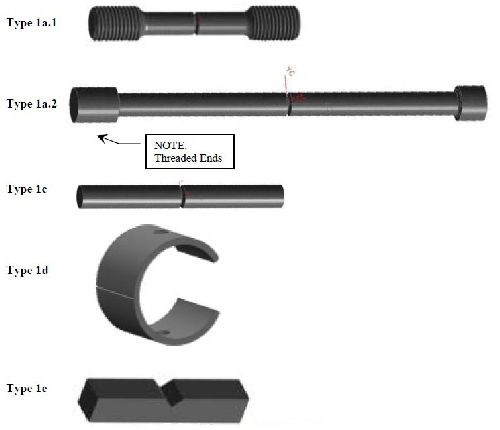

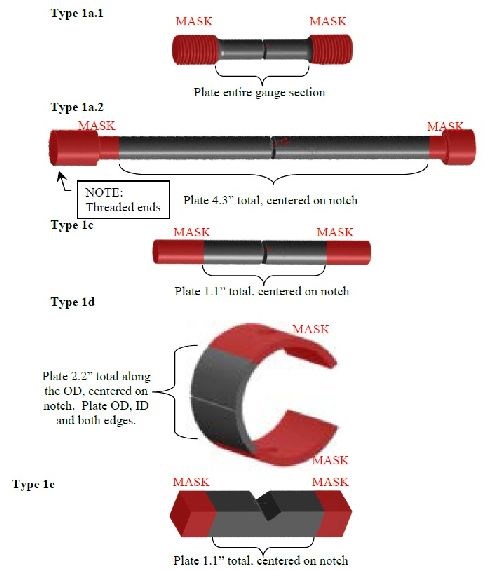

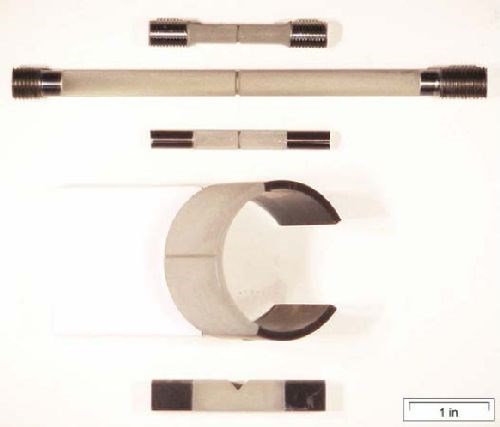

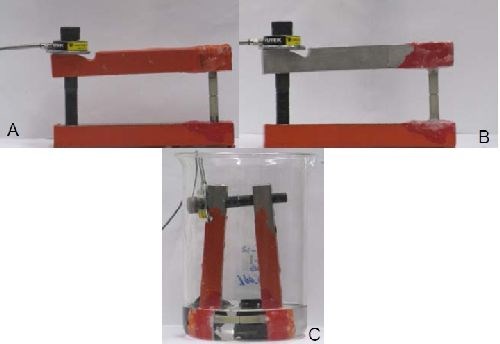

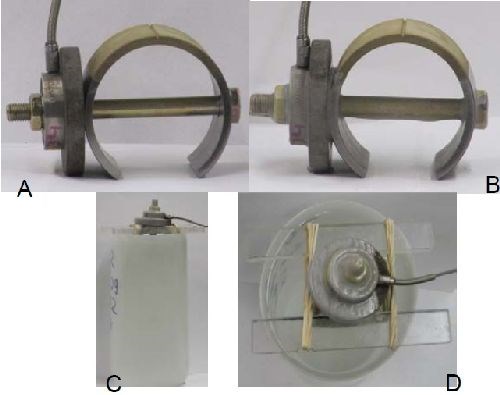

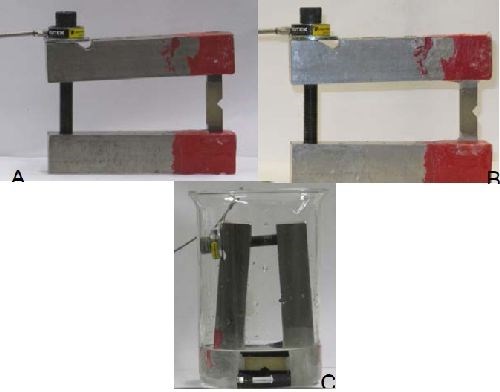

A design of experiment (DOE) approach was used over a range of material strength for both air-melted (AMS 6415) and aerospace grade (AMS 6414) 4340 steel, load level and hydrogen environment. Five ASTM F-519 geometries were explored while monitoring load levels to determine a precise time to fracture at a specific notch fracture strength (NFS), material strength and hydrogen emitting environment (NaCl solution). This allowed comparisons across geometry and material to be drawn. Incorporating the failure time, load and stress levels into the failure models yielded predictive equations over broad parameter ranges. Reliable predictions of hydrogen sensitivity under specific conditions were then realized.

Ultimately, this work aims at evaluating the most prospective environmentally-friendly maintenance chemicals and cadmium alternative coatings that have their use limited by the perceived risk of hydrogen embrittlement. In subsequent years, this work will evaluate the prospective chemicals and coatings over a range of material strength, load level and hydrogen emitting environment which will demonstrate hydrogen sensitivity over parameter ranges, while developing life prediction models for each case. This should greatly increase the applications for which the replacements will be considered, as the models provide the acceptability criteria for the parameters specific to each application.

Keywords: Hydrogen embrittlement testing, hydrogen embrittlement prediction, high strength steels.

• T2 = 158 ± 5 ksi (153-163 ksi)

• T3 = 210 ± 5 ksi (205-215 ksi)

• T4 = 262 ± 5 ksi (257-267 ksi)

• T5 = 280 ± 5 ksi (275-285 ksi)

• T2 = 75 + 6 tensiles

• T3 = 180 + 6 tensiles

• T4 = 75 + 6 tensiles

• T5 = 45 + 6 tensiles

Table 1 - Temper lot quantities.

Temper Lot No. | Strength Target, ksi | No. of specimens | |||||||

1a.1 | 1a.2 | 1c | 1d | 1e | Total | + | Tensiles | ||

T1 | 140 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 30 | + | 6 |

T2 | 158 | 15 | 15 | 15 | 15 | 15 | 75 | + | 6 |

T3 | 210 | 36 | 36 | 36 | 36 | 36 | 180 | + | 6 |

T4 | 262 | 15 | 15 | 15 | 15 | 15 | 75 | + | 6 |

T5 | 280 | 9 | 9 | 9 | 9 | 9 | 45 | + | 6 |

Condition | -α | ̶ | 0 | + | +α |

Strength, ksi | 140 | 158 | 210 | 262 | 280 |

Test load, %NFS | 40 | 45 | 60 | 75 | 95 |

NaCl, wt% | 1.25E-05 | 0.01 | 0.50 | 2.36 | 3.50 |

The design of experiment approach was refined with preliminary ruggedness and risk reduction efforts at Boeing Mesa, with technical assistance from Boeing St. Louis, Seattle, and ARL. Typical of DoEs, it consisted of three test portions, a linear portion, a quadratic portion and a confirmation portion. The example matrix is as presented in Tables 3 thru 5 with the condition values corresponding to Table 2. These experiments aided the development of appropriate boundary conditions for the larger effort.

Repeat entire matrix 2× for 1a.1, 1a.2, 1c, 1d and 1e | Run ID | A | B | C | Run order |

Strength, ksi | Test load, %NFS | NaCl, wt% | |||

Linear portion | L1 | ̶ | ̶ | ̶ | Random |

L2 | ̶ | ̶ | + | ||

L3 | ̶ | + | ̶ | ||

L4 | ̶ | + | + | ||

L5 | + | ̶ | ̶ | ||

L6 | + | ̶ | + | ||

L7 | + | + | ̶ | ||

L8 | + | + | + | ||

Center points | C1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

C2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||

C3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||

C4 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||

C5 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||

C6 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

Repeat Q1-Q6 5× for 1a.1, 1a.2, 1c, 1d and 1e | Run ID | A | B | C | Run order |

Strength, ksi | Test load, %NFS | NaCl, wt% | |||

Not replicated | C7 | 0 | 0 | 0 | First |

Quadratic portion | Q1 | +α | 0 | 0 | Random |

Q2 | -α | 0 | 0 | ||

Q3 | 0 | +α | 0 | ||

Q4 | 0 | -α | 0 | ||

Q5 | 0 | 0 | +α | ||

Q6 | 0 | 0 | -α | ||

Not replicated | C8 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Last |

| Run ID | A | B | C | Run order |

Strength, ksi | Test load, %NFS | NaCl, wt% | |||

Confirmation portion | 1 | Varied, depending on outcome of Linear, Center and Quadratic Results | Random | ||

2 | |||||

3 | |||||

4 | |||||

5 | |||||

6 | |||||

7 | |||||

8 | |||||

9 | |||||

10 | |||||

11 | |||||

12 | |||||

13 | |||||

14 | |||||

15 | |||||

16 | |||||

After the linear and center point data runs were completed, initial calculations were made for the predictive model equations. Those initial models were utilized to choose confirmation runs to be researched. The confirmation run results were then incorporated into refining the initial working model.

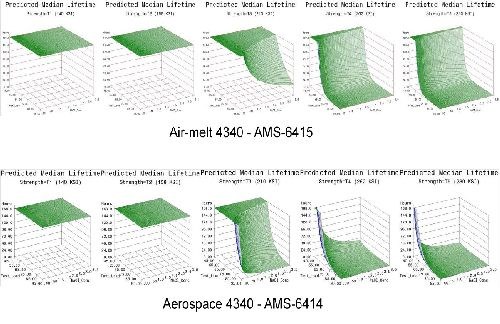

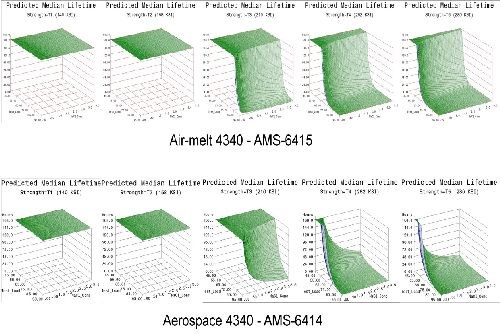

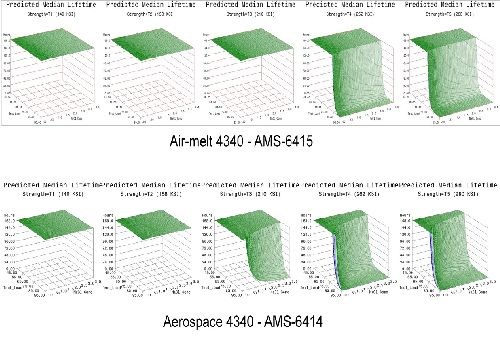

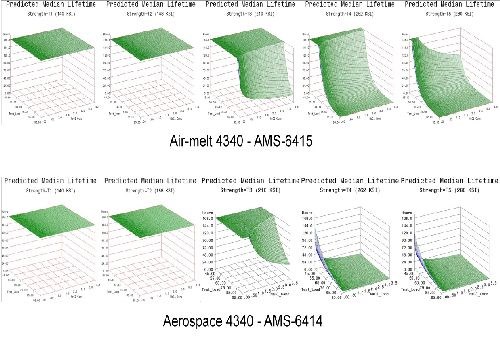

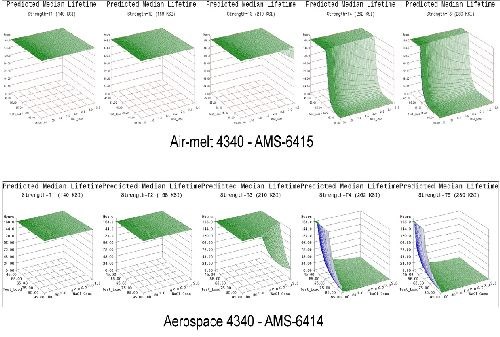

As stated previously, upon conclusion of the linear, center and quadratic test runs, preliminary life prediction models were created. These models were then used in the confirmation test portion of the matrix to choose appropriate parameters to both enhance and verify the model. Final life prediction equations and three dimensional models were created after the incorporation of the confirmation data.

Air-melted SAE-AMS-6415 steel

1a.1 Preliminary Model

where

Offset = σ×ln(-ln(1-P)) (4a)

for which

T = time to event. It is either the time to failure or the time to the end of the experiment (168 hr).

P = the predicted percentile. At a P of 70%, 70% of the failures would be above the curve and 30% would fall below the curve generated.

σ = 1/Weibull shape parameter. Weibull shape parameter = 0.579.

- A negative value of the coefficient is indicative of a shorter lifetime as the variable increases.

- Weibull shape < 1 → hazard rate (failure rate) decreases as time increases.

- Infant mortality. After initial early failures the survival improves with age.

1a.1 Confirmation Model

ln(T) = 6.77-4.98×Str-1.29×Load-0.93×NaCl-3.66×Str×Load+Offset (5)

Weibull shape parameter = 0.567

1a.2 Preliminary Model

ln(T) = 9.09-5.49×Str-7.39×Load-1.39×NaCl+Offset (6)

Weibull shape parameter = 0.377

1a.2 Confirmation Model

ln(T) = 8.75-5.90×Str-6.53×Load-1.33×NaCl+Offset (7)

Weibull shape parameter = 0.397

1c Preliminary Model

ln(T) = 19.01-11.67×Str-9.93×Load-0.88×NaCl+Offset (8)

Weibull shape parameter = 0.343

1c Confirmation Model

ln(T) = 20.91-10.53×Str-11.30×Load-1.25×NaCl+Offset (9)

Weibull shape parameter = 0.278

1d Preliminary Model

ln(T) = 7.83-4.04×Str-3.54×Load-1.01×NaCl+Offset (10)

Weibull shape parameter = 0.515

1d Confirmation Model

ln(T) = 7.68-4.12×Str-3.08×Load-6.04×NaCl+Offset (11)

Weibull shape parameter = 0.546

1e Preliminary Model

ln(T) = 12.31-7.45×Str-6.45×Load-0.97×NaCl+Offset (12)

Weibull shape parameter = 0.505

1e Confirmation Model

ln(T) = 13.14-8.16×Str-6.58×Load-0.73×NaCl+Offset (13)

Weibull shape parameter = 0.493

Vacuum Arc Re-melted SAE-AMS-6414 steel

1a.1 Preliminary Model

ln(T) = 5.20-4.79×Str-2.22×Load-1.73×NaCl-1.24×Str×Str+Offset (14)

Weibull shape parameter = 1.090

1a.1 Confirmation Model

ln(T) = 5.66-5.28×Str-2.82×Load-1.52×NaCl-1.29×Str×Str+Offset (15)

Weibull shape parameter = 0.913

1a.2 Preliminary Model

ln(T) = 7.90-5.20×Str-3.00×Load-1.77×NaCl+Offset (16)

Weibull shape parameter = 0.643

1a.2 Confirmation Model

ln(T) = 7.69-7.73×Str-2.93×Load-1.57×NaCl-2.40×Str×Str+Offset (17)

Weibull shape parameter = 0.644

1c Preliminary Model

ln(T) = 11.35-8.27×Str-5.96×Load-3.2×NaCl-2.5×Str×Str+Offset (18)

Weibull shape parameter = 0.548

1c Confirmation Model

ln(T) = 11.6-8.19×Str-6.49×Load-2.92×NaCl-2.34×Str×Str+Offset (19)

Weibull shape parameter = 0.541

1d Preliminary Model

ln(T) = 6.63-6.85×Str-1.40×Load-0.95×NaCl-2.80×Str×Str+Offset (20)

Weibull shape parameter = 1.234

1d Confirmation Model

ln(T) = 6.52-6.58×Str-1.08×Load-0.99×NaCl-2.60×Str×Str+Offset (21)

Weibull shape parameter = 1.237

1e Preliminary Model

ln(T) = 9.08-11.04×Str-1.68×Load-2.21×NaCl-4.29×Str×Str+Offset (22)

Weibull shape parameter = 0.646

1e Confirmation Model

ln(T) = 8.92-9.56×Str-1.93×Load-2.18×NaCl-3.26×Str×Str+Offset (23)

Weibull shape parameter = 0.695

- Life prediction models were developed that accurately represent the expected hydrogen sensitivity over the range of parameters explored for air-melted and vacuum arc re-melted 4340 steel.

- The trends observed in the data were reasonably consistent across all test geometries. Sensitivity increases with applied load, material strength and to a lesser degree NaCl concentration.

- Applied stress has the most direct effect on hydrogen sensitivity, while material strength is a close second. Increasing the value of either parameter directly heightens the sensitivity to hydrogen.

- 4340 steel does not appear susceptible to hydrogen absorbed from environmental corrosion below the 160 ksi strength level.

- High residual stress levels (40-50% of UTS) are capable of causing hydrogen embrittlement without further applied system stresses.

- The 1d test geometry proved the most sensitive to hydrogen and also conducive to testing multiple specimens in various environments without requiring test load frames.

- Vacuum arc re-melted steel was more susceptible to hydrogen than air-melted 4340 steel in this environment.

- Vacuum arc re-melted steel was more sensitive to NaCl concentration than air-melted 4340 steel.

- SAE-AMS 6415S-2007, Steel, Bars, Forgings, and Tubing 0.80 Cr - 1.8 Ni - 0.25 Mo (0.38 - 0.43 C), SAE World Headquarters, Warrendale, PA, 2007.

- SAE-AMS 6414K-2007, Steel, Bars, Forgings, and Tubing 0.80 Cr - 1.8 Ni - 0.25 Mo (0.38 - 0.43 C) (SAE 4340) Vacuum Consumable Electrode Remelted, SAE World Headquarters, Warrendale, PA, 2007.

- ASTM F-519-10, Standard Test Method for Mechanical Hydrogen Embrittlement Evaluation of Plating/Coating Processes and Service Environments, ASTM International, West Conshohocken, PA, 2010.

- MIL-STD-870C, Department of Defense Standard Practice: Cadmium Plating, Low Embrittlement, Electro-Deposition, 2009.

Related Content

Chicago-Based Anodizer Doubles Capacity, Enhancing Technology

Chicago Anodizing Company recently completed a major renovation, increasing its capacity for hardcoat anodizing and Type II anodizing.

Read MoreA Smooth Transition from One Anodizing Process to Another

Knowing when to switch from chromic acid anodizing to thin film sulfuric acid anodizing is important. Learn about why the change should be considered and the challenges in doing so.

Read MoreUnderstanding PEO Coatings

Using high-speed cameras and back side illumination (BSI) sensor technology to analyze plasma electrolytic oxidation.

Read MoreRead Next

Education Bringing Cleaning to Machining

Debuting new speakers and cleaning technology content during this half-day workshop co-located with IMTS 2024.

Read MoreDelivering Increased Benefits to Greenhouse Films

Baystar's Borstar technology is helping customers deliver better, more reliable production methods to greenhouse agriculture.

Read MoreEpisode 45: An Interview with Chandler Mancuso, MacDermid Envio Solutions

Chandler Mancuso, technical director with MacDermid Envio discusses updating your wastewater treatment system and implementing materials recycling solutions to increase efficiencies, control costs and reduce environmental impact.

Read More

.jpg;maxWidth=300;quality=90)