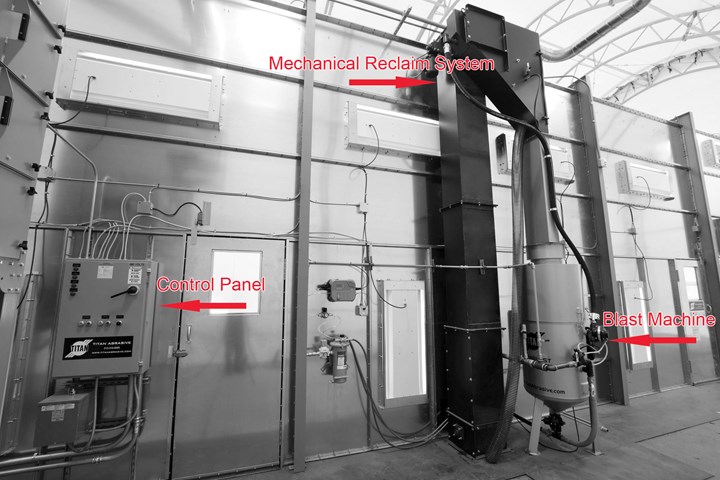

Mechanical reclaim system for blasting operation

Photo Credit: All photos courtesy of Titan Abrasives

Q: I’m considering a reclaim system for my blasting operation, but could use some advice on what to invest in.

In the world of abrasive blasting — a critical process in the product finishing world — reclaimability does not get the credit it deserves.

Take steel grit, the most reclaimable of all blast media. It can be reused upward of 200 times for an initial cost of $1,500 - $2,000 per ton. Compare that to the $300 per ton for blast media like coal slag that is intended for single use, and you can quickly see how reclaimable material can be a better value than some lower-cost materials meant for one-time or limited use.

Reclaiming media

Whether in a blast room or blast cabinet, there are two ways to collect blast media for continuous use: vacuum (pneumatic) recovery systems, and mechanical recovery systems. Each has its strengths as well as limitations, mostly dependent on the type of blast media your operation requires.

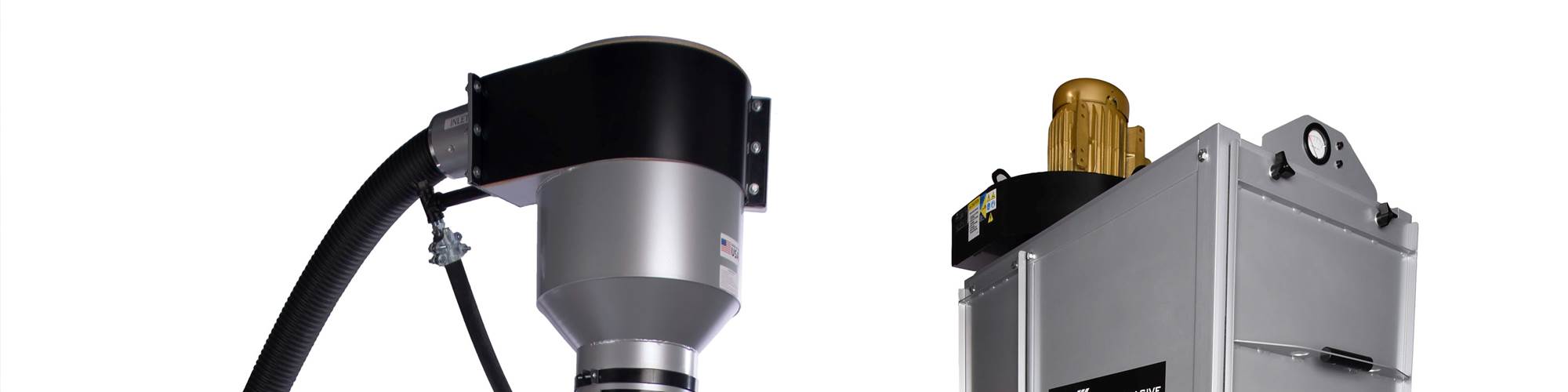

Vacuum Recovery Systems

Titan Vacuum System

Less expensive than mechanical systems, vacuum systems work well with lighter blast media, such as plastic, glass bead, and even some of the finer versions of aluminum oxide. The lower cost is largely because, unlike mechanical systems, they incorporate fewer components overall. What’s more, since a vacuum system does not have any mechanical components, less maintenance is required.

Vacuum systems also offer the convenience of portability. Some vacuum systems can be skid-mounted, which circumvents the need for permanent installation, whether due to aesthetics or limited production space.

There are three basic types of vacuum recovery systems from which to choose. The major difference is when they pick up the spent blast media and the speed at which they do it.

The first type allows the user to perform an entire blast operation; when the job is completed, a vacuum attachment picks up all of the media at one time. This system is helpful because, if your project requires recovery of all blast media, it can reduce issues with media disposal.

The second type is typically found in industrial blasting applications that utilize blast rooms or blast cabinets. In blast room applications, the user typically sweeps or shovels the blast media into a recovery trough at the rear of the blast room, at the end or during the blasting process. The spent media is vacuumed up and carried to a cyclone separator where it is cleaned and returned to the blast machine for reuse. In blast cabinet applications, the media is reclaimed continuously during the blast operation without the user having to perform any additional steps.

In the third option, the spent media is suctioned back in continuously through a vacuum work head, immediately after hitting the surface of the blasted product. While much slower than the previous options, by blasting and suctioning media simultaneously, there will be far less dust generated and less blast media spilled overall. And with less media sitting around exposed, sandblast dust contamination will be greatly reduced.

Overall, the vacuum method is less labor-intensive than the mechanical because it’s easier to sweep up the lighter blast media. However, since vacuum systems cannot effectively suction up more weighty media, the use of materials such as steel grit and steel shot — some of the most reusable substances — is virtually excluded. Another drawback is speed; if a company is doing a high volume of blasting and recovery, vacuum systems can create a considerable bottleneck.

Some companies do provide a full-floor vacuum system, with multiple chambers that cycle from one to another. While faster than the systems previously described, it is still slower than the mechanical version.

Mechanical Recovery Systems

Mechanical recovery is ideal for high-production needs as it can accommodate any size recovery area. Plus, mechanical blast media recovery systems can handle the heaviest media, steel grit/shot. A mechanical system is also much faster than the typical vacuum system, making it a natural choice for high-production blasting and recovery.

The bucket elevator is at the heart of any mechanical system. It comes equipped with a front-loading hopper, into which the recovered blast media is swept or shoveled. It’s constantly moving, with each bucket scooping up some of the recovered blast media. The media is subsequently cleaned through a rotary drum and/or air wash separator, which splits up reusable media from dust, debris, and other particulate matter.

The simplest configuration is to buy a bucket elevator and bolt it to the ground, leaving the hopper above ground. However, with the hopper about two feet above the ground in this case, it can be a daunting task to get the steel grit into the hopper, given that a shovelful can weigh from 60-80 pounds.

The optimal arrangement has both the bucket elevator and (a slightly different) hopper recessed into a pit. The bucket elevator is on the outside of the blast room, while the hopper is inside, level with the concrete floor. The excess blast media can then be swept into the hopper rather than shoveled — a far less taxing job.

Auger within a mechanical reclaim system. The auger will push the blast media into the hopper to be fed back into the blast machine.

If the blast room is especially large, augers can be added to the equation. The most common addition is a cross auger, installed across the back of the room. This allows employees to simply push (or even blow, with compressed air) the spent blast media to the back wall. Whatever part of the auger the media is pushed into, it will be transported back to the bucket elevator.

Additional augers can be installed in a “U” or an “H” formation. There is even a full-floor option, with multiple augers feeding to the cross auger, and the entire concrete floor replaced by heavy-duty grating.

Conclusion

For a small shop that wants to save money, is willing to use lighter media in their blasting operation, and isn’t worried about production speed, a vacuum system can be just the ticket. It can even be a solid choice for a larger company that does limited blasting and doesn’t need a system capable of keeping up with a high-volume blasting process. Conversely, mechanical systems work best with heavier media, where cost is not a major factor, but speed is.

About the Author

Brandon Acker

Brandon Acker is president of Titan Abrasive Systems, one of the premier designers and manufacturers of abrasive blast rooms, cabinets, and associated equipment. Visit titanabrasive.com.

Related Content

Top Reasons to Switch to a Better Cleaning Fluid

Venesia Hurtubise from MicroCare says switching to the new modern cleaning fluids will have a positive impact on your cleaning process.

Read MoreCorrosion Resistance Testing for Powder Coating

Salt spray can be useful to help compare different pretreatment methods and coatings but it does not tell us much about the corrosion resistance of a part over time in the field. Powder coating expert Rodger Talbert offers insights into how to get a better idea of how to improve a part’s corrosion resistance in the real world.

Read MoreUnderstanding and Managing White Spots on Anodized Aluminum

Having trouble with spotting defects when anodizing? Taj Patel of Techevon LLC offers a helpful overview of the various causes of white spots and potential solutions.

Read MoreLiquid Chrome Vs. Chromic Acid Flake

Contemplating how to continue offering chromic acid services in an increasingly stringent regulatory world? Liquid chrome products may be the solution you’re looking for.

Read MoreRead Next

Glass Bead Blasting as Plating Pretreatment

What are the best practices for using blasting in preparation for plating? Angelo Magrone of Bales Metal Surface Solutions discusses the ins and outs of glass bead blasting.

Read MoreHow to Maintain Vibratory Finishing Media

Vibratory finishers and vibratory media require cleaning and maintenance to function properly. Here are tips to keep yours running well.

Read MoreEpisode 19: Brandon Acker, Titan Abrasive Systems

Brandon Acker of Titan Abrasive Systems offers insights for blasting best practices.

Read More

.jpg;maxWidth=300;quality=90)