Electrocodeposition of MCrAlY Coatings for Advanced Gas Turbine Applications - 5th Quarterly Research Report

The objective of the work is to study and optimize the MCrAlY electrocodeposition process to improve the coating oxidation/corrosion performance. In this quarter, work focused on preparation and characterization of CrAlY-based alloy powders for the planned research activities in Task 2: The Effect of CrAlY Particle size on CrAlY Particle Incorporation.

Editor’s Note: This NASF-AESF Foundation research project report covers the fifth quarter of project work (January-March, 2019) on an AESF Foundation Research project at the Tennessee Technological University, Cookeville, Tennessee. A printable PDF version of this report is available by clicking HERE.

Summary: In the first quarter of Year 2, we focused on preparation and characterization of CrAlY-based alloy powders for the proposed research activities in Task 2. A variety of powders were collected including commercial gas-atomized CrAlY and CoNiCrAlY powders, and laboratory ball-milled CrAlY-based powders. To further control the particle size distribution of the ball-milled powder, a water elutriation method was used to separate the particles smaller than 5 µm and larger than 20 µm from the original powder. This method utilizes the relationship between the particle size and terminal velocity to sort out particles of different sizes. By adjusting the flow velocity of the rising fluid, different sized particles were collected. Particle size analysis was carried out using a laser diffractor, and the density of the alloy powder was determined using a pycnometer. The morphologies of the different types of powders were characterized using scanning electron microscopy.

Technical report

I. Introduction

To improve high-temperature oxidation and corrosion resistance of critical superalloy components in gas turbine engines, metallic coatings such as diffusion aluminides or MCrAlY overlays (where M = Ni, Co or Ni+Co) have been employed, which form a protective oxide scale during service.1 The state-of-the-art techniques for depositing MCrAlY coatings include electron beam-physical vapor deposition (EB-PVD) and thermal spray processes.1 Despite the flexibility they permit, these techniques remain line-of-sight which can be a real drawback for depositing coatings on complex-shaped components. Further, high costs are involved with of the EB-PVD process.2 Several alternative methods of making MCrAlY coatings have been reported in the literature, among which electro-codeposition appears to be a more promising coating process.

Electrolytic codeposition (also called “composite electroplating”) is a process in which fine powders dispersed in an electroplating solution are codeposited with the metal onto the cathode (specimen) to form a multiphase composite coating.3,4 The process for fabrication of MCrAlY coatings involves two steps. In the first step, pre-alloyed particles containing elements such as chromium, aluminum and yttrium are codeposited with the metal matrix of nickel, cobalt or (Ni,Co) to form a (Ni,Co)-CrAlY composite coating. In the second step, a diffusion heat treatment is applied to convert the composite coating to the desired MCrAlY coating microstructure with multiple phases of β-NiAl, γ-Ni, etc.5

Compared to conventional electroplating, electro-codeposition is a more complicated process because of the particle involvement in metal deposition. It is generally believed that five consecutive steps are engaged:3,4 (i) formation of charged particles due to ions and surfactants adsorbed on particle surface, (ii) physical transport of particles through a convection layer, (iii) diffusion through a hydrodynamic boundary layer, (iv) migration through an electrical double layer and finally, (v) adsorption at the cathode where the particles are entrapped within the metal deposit. The quality of the electro-codeposited coatings depends upon many interrelated parameters, including the type of electrolyte, current density, pH, concentration of particles in the plating solution (particle loading), particle characteristics (composition, surface charge, shape, size), hydrodynamics inside the electroplating cell, cathode (specimen) position, and post-deposition heat treatment if necessary.3-6

There are several factors that can significantly affect the oxidation and corrosion performance of the electrodeposited MCrAlY coatings, including: (i) the volume percentage of the CrAlY powder in the as-deposited composite coating, (ii) the CrAlY particle size/distribution, and (iii) the sulfur level introduced into the coating from the electroplating solution. This three-year project aims to optimize the electro-codeposition process for improved oxidation/corrosion performance of the MCrAlY coatings. The three main tasks are as follows:

- Task 1 (Year 1): Effects of current density and particle loading on CrAlY particle incorporation.

- Task 2 (Year 2): Effect of CrAlY particle size on CrAlY particle incorporation.

- Task 3 (Year 3): Effect of electroplating solution on the coating sulfur level.

In this reporting period, we focused on preparation and characterization of CrAlY-based alloy powders for the proposed research activities in Task 2.

II. Background

Electrochemical composite plating, as a versatile and convenient fabrication process route for producing composite coatings, has gained renewed interest, particularly with the emergence of nanostructured materials. In addition to the excellent review papers published in the 1990s by Celis, et al.,7-9 several overviews have been published in recent years, summarizing the most recent developments in this field.3,4,10,11

In Year 1 of this project, we studied the effects of several important electro-codeposition parameters on the CrAlY(Ta) particle incorporation in the as-deposited Ni-CrAlY(Ta) coatings, including current density and concentration of particles in the plating solution (particle loading). The current density was varied between 5 and 60 mA/cm2. For ball-milled CrAlY powders with an irregular shape, an increase in particle incorporation from 25 to 40 vol% was observed when the current density was decreased from 60 to 5 mA/cm2. However, for spherical CrAlY powders made by gas atomization, the current density showed very little influence on particle incorporation (40-43 vol%). In general, the increase in particle loading led to an increase in particle incorporation until it reached a plateau, which is consistent with the Langmuir adsorption isotherm on the electrode surface.

In addition to the electro-codeposition parameters, the particle properties (e.g., size, shape, and density) can affect the particle incorporation in the composite coatings. As an example, our results showed that heavier CrAlYTa powders (with a density of 5.5 g/cm3) exhibited higher particle incorporation than the CrAlY powders without Ta (4.5 g/cm3). Furthermore, the geometry of the particles (spherical vs. irregular) affected the CrAlY particle incorporation.

However, the particle properties are the least controllable process parameters, as the chosen particle material and (commercial) availability often restrict particle shape and size.11 In Year 2 of this project, we will mainly focus on the effect of CrAlY particle size on the CrAlY particle incorporation.

III. Experimental Procedure

3.1. Powder preparation

A variety of powders were prepared including gas-atomized CrAlY and CoNiCrAlY powders, as well as ball-milled CrAlY-based powders. The atomized CrAlY and CoNiCrAlY powders were purchased from Sandvik Materials Technology and Phoenix Scientific Industries Ltd, respectively. The ball-milled powders were made at TTU from high purity metals using an arc-melter, followed by ball-milling in a high-energy ball mill for 30-45 min. Both atomized and ball-milled powders were sieved through a 20-μm screen (625 mesh).

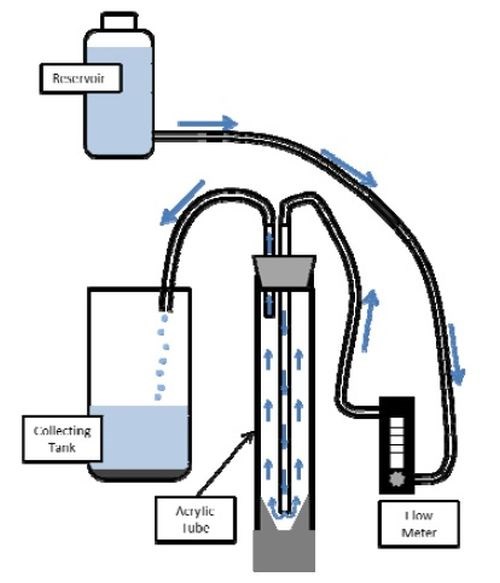

Figure 1 - Diagram of the water elutriation system.

To further control the particle size distribution of the ball-milled powder, a water elutriation method12 was used to separate the particles smaller than 5 μm and larger than 20 μm from the original powder. This method utilizes the relationship between the particle size and terminal velocity to sort out particles of different sizes. As shown in Fig. 1, water was fed upward in a vertical column at a controlled flow velocity. Particles that were too small with a terminal velocity less than the flow velocity were then separated from the vertical column. By adjusting the flow velocity of the rising fluid, different size particles were collected.

3.2. Powder characterization

Particle size analysis was carried out using a Malvern Mastersizer 2000 Laser diffractor. The density of the alloy powder was determined using a pycnometer (Micromeritics AccuPyc II 1340 Pycnometer). The morphologies of the different types of powders were characterized using scanning electron microscopy (SEM).

IV. Results and Discussion

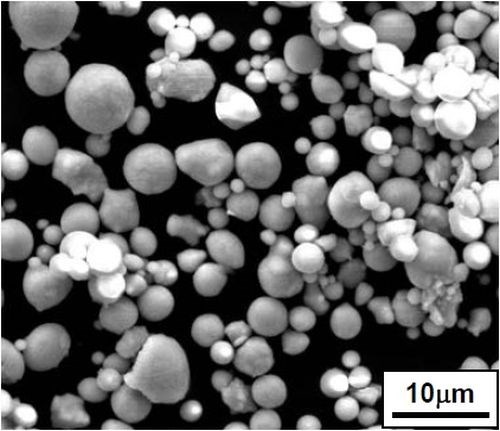

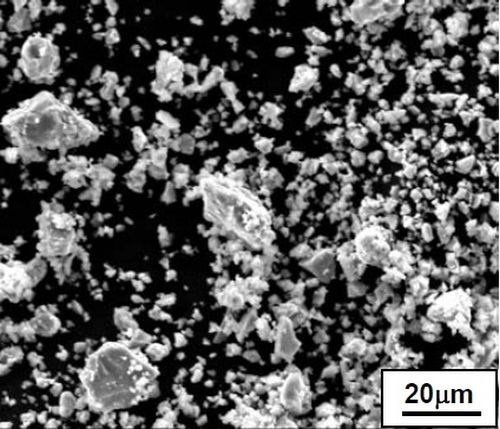

Figure 2 shows the particle morphologies of the ball-milled and gas-atomized CrAlY powders. Even though the two powders had similar chemical compositions, they exhibited quite different shapes. The atomized particles were mostly spherical, while the ball-milled powders were more irregular.

(a)

(b)

Figure 2 - Particle morphologies of (a) atomized CrAlY vs. (b) ball-milled powders.

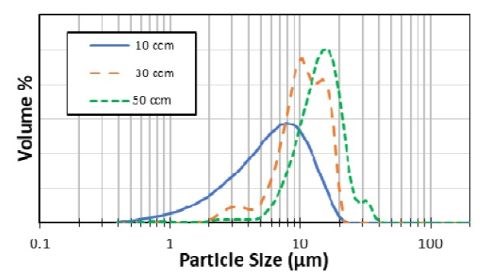

Figure 3 compares the particles size distributions for different flow rates used in the water elutriation system. These results indicate that a particle size distribution of 5 to 20 μm could be achieved by discarding the smaller particles through an initial flow rate of 10 ccm and collecting the particles of with a subsequent increase in flow rate of 30 ccm.

Figure 3 - Particle size distribution vs. the flow rate used in the water elutriation method.

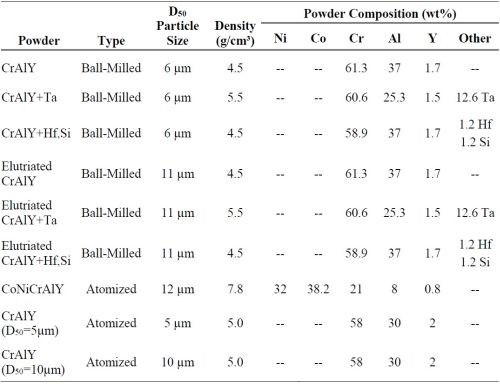

Some of the as-received powders exhibited a relatively broad particle size range, e.g., 4-150 μm for the atomized CoNiCrAlY powder. After sieving, the atomized powder had a range of 4 to 20 μm. The chemical composition, density and mean particle size of all the powders are summarized in Table 1. Particle size and density can change the magnitude of forces acting on the particle both while suspended in the solution and when in contact with the component surface. When a sedimentation or barrel configuration is used, the velocity of the particle is dictated by a balance of gravitational forces and hydrodynamic drag forces. Hence, the particle size and density are expected to affect the particle incorporation in the electro-codeposited coatings. The increase of particle velocity can in turn increase the particle transport to the component surface and in turn increase the particle concentration at the surface.

Table 1 - Chemical composition, mean particle size, and density of the pre-alloyed CrAlY(Ta) and CoNiCrAlY powders.

References

1. G.W. Goward, Surf. Coat. Technol., 108-109, 73-79 (1998).

2. A. Feuerstein, et al., J. Therm. Spray Technol., 17 (2), 199-213 (2008).

3. C.T.J. Low, R.G.A. Wills and F.C. Walsh, Surf. Coat. Technol., 201 (1-2), 371-383 (2006).

4. F.C. Walsh and C. Ponce de Leon, Trans. Inst. Metal Fin., 92 (2), 83-98 (2014).

5. Y. Zhang, JOM, 67 (11), 2599-2607 (2015).

6. B.L. Bates, J.C. Witman and Y. Zhang, Mater. Manuf. Process, 31 (9), 1232-1237 (2016).

7. J.R. Roos, J.P. Celis, J. Fransaer and C. Buelens, JOM, 42 (11), 60-63 (1990).

8. J.P. Celis, J.R. Roos, C. Buelens and J. Fransaer, Trans. Inst. Met. Finish., 69 (4), 133-139 (1991).

9. C. Buelens, J. Fransaer, J.P. Celis and J.R. Roos, Bull. Electrochem., 8 (8), 371-375 (1992).

10. A. Hovestad and L.J.J. Janssen, J. Appl. Electrochem., 25 (6), 519-527 (1995).

11. A. Hovestad and L.J.J. Janssen, “Electroplating of Metal Matrix Composites by Codeposition of Suspended Particles,” in Modern Aspects of Electrochemistry, B.E. Conway, C.G. Vayenas, R.E. White and M.E. Gamboa-Adelco, Eds. Springer, Boston, MA, (2005); pp. 475-532.

12. L.R. Follmer and A.H. Beavers, J. Sedimentary Res. (formerly J. Sedimentary Petrology), 43 (2), 544-549 (1973).

Past project reports

1. Quarter 1 (January-March 2018): Summary: NASF Report in Products Finishing; NASF Surface Technology White Papers, 82 (12), 13 (September 2018); Full paper: http://short.pfonline.com/NASF18Sep1.

2. Quarter 2 (April-June 2018): Summary: NASF Report in Products Finishing; NASF Surface Technology White Papers, 83 (1), 13 (October 2018); Full paper: http://short.pfonline.com/NASF18Oct1.

3. Quarter 3 (July-September 2018): Summary: NASF Report in Products Finishing; NASF Surface Technology White Papers, 83 (3), 15 (December 2018); Full paper: http://short.pfonline.com/NASF18Dec1.

4. Quarter 4 (October-December 2018): Summary: NASF Report in Products Finishing; NASF Surface Technology White Papers, 83 (7), 11 (April 2019); Full paper: http://short.pfonline.com/NASF19Apr1.

About the author

Dr. Ying Zhang is Professor of Mechanical Engineering at Tennessee Technological University, in Cookeville, Tennessee. She holds a B.S. in Physical Metallurgy from Yanshan University (China)(1990), an M.S. in Materials Science and Engineering from Shanghai University (China)(1993) and a Ph.D. in Materials Science and Engineering from the University of Tennessee (Knoxville)(1998). Her research interests are related to high-temperature protective coatings for gas turbine engine applications; materials synthesis via chemical vapor deposition, pack cementation and electrodeposition, and high-temperature oxidation and corrosion. She is the author of numerous papers in materials science and has mentored several Graduate and Post-Graduate scholars.

Jason C. Whitman is a Ph.D. student in the Department of Mechanical Engineering, Tennessee Technological University, in Cookeville, Tennessee. His primary work is involved with the AESF Foundation Research Project R-119, Electro-codeposition of MCrAlY Coatings for Advanced Gas Turbine Applications.

*Corresponding author:

Dr. Ying Zhang, Professor

Department of Mechanical Engineering

Tennessee Technological University

Cookeville, TN 38505-0001

Tel: (931) 372-3265

Fax: (931) 372-6340

Email: yzhang@tntech.edu

Related Content

Products Finishing Reveals 2024 Qualifying Top Shops

PF reveals the qualifying shops in its annual Top Shops Benchmarking Survey — a program designed to offer shops insights into their overall performance in the industry.

Read MoreNanotechnology Start-up Develops Gold Plating Replacement

Ag-Nano System LLC introduces a new method of electroplating based on golden silver nanoparticles aimed at replacing gold plating used in electrical circuits.

Read MoreAn Overview of Electroless Nickel Plating

By definition, electroless plating is metal deposition by a controlled chemical reaction.

Read More3 Tests to Ensure Parts are Clean Prior to Plating

Making sure that all of the pre-processing fluids are removed prior to plating is not as simple as it seems. Rich Held of Haviland Products outlines three tests that can help verify that your parts are clean.

Read MoreRead Next

A ‘Clean’ Agenda Offers Unique Presentations in Chicago

The 2024 Parts Cleaning Conference, co-located with the International Manufacturing Technology Show, includes presentations by several speakers who are new to the conference and topics that have not been covered in past editions of this event.

Read MoreEpisode 45: An Interview with Chandler Mancuso, MacDermid Envio Solutions

Chandler Mancuso, technical director with MacDermid Envio discusses updating your wastewater treatment system and implementing materials recycling solutions to increase efficiencies, control costs and reduce environmental impact.

Read MoreEducation Bringing Cleaning to Machining

Debuting new speakers and cleaning technology content during this half-day workshop co-located with IMTS 2024.

Read More