Lean Manufacturing in Anodizing Operations

Here’s how one company applied lean manufacturing principles in its anodizing plant.

Jared Bringhurst is president of Futura Industries, a division of Bonnell Aluminum, a leading manufacturer of custom-fabricated and finished aluminum extrusions. Under Bringhurst’s operations leadership, Futura improved the quality of its products and on-time delivery in the extrusion industry, while most recently overhauling its anodizing facility. Bringhurst shared Futura’s successes at a recent Aluminum Anodizing Council conference and writes about it here.

This is an expanded case study on lean manufacturing and the benefits achieved through the application of specific lean tools and concepts in an anodizing and manufacturing environment, as we have seen at Futura Industries.

In most cases, an organization does not have to look too far or too deep to identify streams of waste: excess motion of employees or equipment; defective material; employees or equipment waiting; excess inventory; over-production; over-processing; and transportation of material from one location to another.

Often, the people who have worked for years in environments with these forms of waste have become accustomed to seeing or recognizing that there is an opportunity to work more efficiently. An example could be something as simple as a garbage can placed 15 feet from where an operator performs the bulk of his tasks on a machine. These scenarios exist in almost every organization. The question is, how do we eliminate them?

Introductory Phase

We identified and attended several off-site training camps, including the Lean Institute in Massachusetts and a Toyota Production Systems (TPS) course in Kentucky. The Industryweek Best Plants Conference showcased a variety of lean tools used by winners of the best plants designation, and these presentations provided additional detail and help for our organization. We also interviewed several consulting agencies and settled on a local consulting group well-versed and experienced at both training and implementing lean principles. What we quickly realized was that we needed not only to educate our senior executive team, but we also needed to educate every individual team member within our organization. It took time, money and energy. It was a very difficult and challenging process, but in the end, there was no question it was the right thing to do and well worth the investment. The training was excellent, the concepts and lean principles became clear, and the root cause of our problems and issues began to manifest themselves in ways that seemed extremely, almost embarrassingly, obvious.

After nearly six months of training our senior executive team; sales force; and finance, purchasing, production, maintenance, engineering and logistics teams, we began to look at the underlying structure of our business systems and processes. We looked at every item produced, and its specific routing or sequence of process steps. There were hundreds of iterations or sequences by which all of our products were made, and we realized that they really needed to be organized into a much better group of part families.

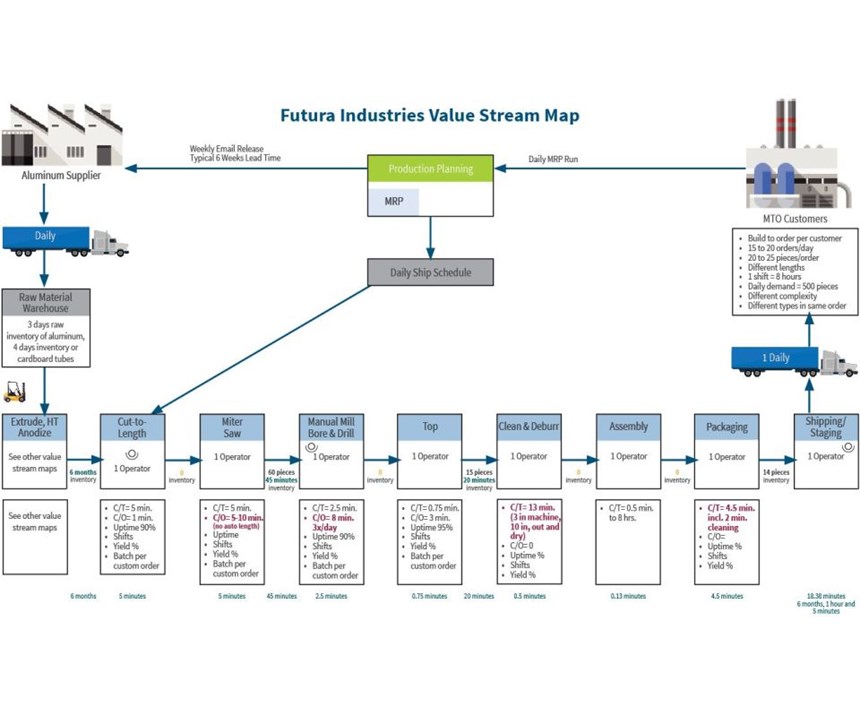

As we began to sort 11,000 different SKUs, we were able to narrow down eight different high-volume paths, which we later named “value streams.” There were literally hundreds of smaller path sequences, which we named “value creeks,” and there were two large shared resources within the majority of routings, which we named ”monuments” and defined as a solid shared resource spanning multiple value streams. This configuration was defined as a specific path or sequence of operations where value is added to the material in a specific way. We also tried to group customers into value streams rather than items.

Implementation Phase

With our entire organization educated and trained on lean manufacturing, and with monuments and value streams identified and defined, we were ready to implement and trial a variety of the available lean tools. We modified our personnel structure to accommodate the new layout of our value streams, appointing a facilitator and a value stream engineer for each; in some cases, an engineer or facilitator would have responsibilities for multiple value streams.

The value stream engineer developed a value stream map, both current-state and future-state, based on goals for what we wanted to accomplish, and then we identified kaizen blitzs or areas of opportunity to help us accomplish those goals. The majority of these goals centered around meeting promise dates, improving quality, increasing capacity, improving productivity, reducing cost and occupying less physical floor space.

The goals for each area were displayed and prioritized. Our desire was to start out with a kaizen event that would lead to a trophy area, or an area that would stand as an example of what the lean process can achieve. We set dates and identified individuals who should be invited to attend the different respective kaizen events.

Application of Lean Tools and Methodologies

Once we had identified and defined value streams, and set up and carried out our first group of kaizen events, we realized how to use other lean tools that facilitated a variety of other lean improvements, both large and small, throughout all areas of our operation.

Specifically in anodizing, we implemented 5S, point-of-use storage (POUS), kaizen, standardized work, kanbans and cellular/flow improvements. Our teams developed shadow boards for our housekeeping supplies; labeled and organized our racking stations; and moved chemicals and inspection tools such as our isoscope, seal testing and color meters right to the point of use. Visual controls and kanbans were added so that we replenished racks, clamps, rags, personal protective equipment, chemicals and so on. We shifted very much to a continuous-improvement-minded culture, and it continues to evolve every day. Today, work is staged on carts identified with flags, and a cone on each cart shows the finish of that order and how many hoods that order contains. Our mix is scheduled to optimize our anodizing capacity. The work is delivered to the anodizing operators along with clamps, racks and everything else that operator will need.

When the anodizing line is lacking its next order, a light turns on and a buzzer sounds. The chemistry (when applicable) contains sensors that identify whether rinsing and inclined holding for dripping was properly achieved. While our anodizing line is not fully automated, there have been several additions allowing semi-automation of chemical adds, and statistical feedback for chemistry of the tanks and amperage pulled during an anodizing cycle. Where we have been constrained by available space, we have added spray nozzles for improved rinsing and visual controls to aid process control by our crane operators. When supplies reach a point of needing replenishment, there is a visual control for our water striders to replenish. In the event other supplies are needed, operators can use a touchscreen to order supplies by name, and the order will immediately appear on the water strider’s iPad, along with a timer showing estimated delivery of that item.

All process time is measured from the time the product is racked, anodized and then unracked. Each step is measured and recorded. Visual controls have been added to rectifiers. A green light will indicate the rectifier is supplying electricity. When the cycle nears completion, there is a two-minute warning during which the green light begins to flash. At the conclusion of the cycle, the light stops flashing and turns red, and a buzzer sounds notifying the operator it is time to advance the batch of material. Various improvements to racking have been made over the years as a result of our Waste Stopper program, by which team members suggest solutions for specific waste problems.

In other areas of our facility, we have implemented several Single-Minute Exchange of Die (SMED) kaizens. Our “lean guru” often repeats the phrase, “Flow is king.” We can attest to huge savings based on flow, as we’ve held several area-layout and a few plant-layout kaizens to establish clear linear or cellular paths of flow.

Successes Realized Through Lean

Our initial kaizen event included a complete revision to the layout of our small bent parts value stream area and included two new U-shaped work cells. A new packaging and inspection area resulted in: a 24 percent increase in productivity, 33 percent savings of floor space, elimination of all work in process (WIP) and a reduction in team size from 11 operators to six (the other five moved to other value streams).

We experienced very little pushback from our team on the changes and the philosophy of lean manufacturing, and we attribute that success to the upfront training and our patience on the implementation. The U-shaped work cell had originally been set up in batch formation. Each machine typically required one operator, and that operator would fabricate parts on the machine for an entire shift. Parts would be produced in batches oftentimes taken from a cart and returned to the same cart. The U-shaped work cell was designed to eliminate batch flow, moving to one-piece or two-piece flow, and eliminating all (WIP). Raw material enters the work cell and leaves as a finished product. At the end of the day, there are only raw stock and finished parts possible in the work cell. Also, the cell was designed to use a maximum of two operators, compared to four to five operators required to run the machines prior to our kaizen. The cell was condensed further to eliminate wasted extra steps. A new 10-foot brake press was replaced by a small, used 3-foot brake press, which shaved 7 feet of unnecessary space within the cell. Shadow boards were retrofitted with fewer tools and better POUS.

“Keeping the surgeon at the table” has been another large priority; anything that takes the operator away from his or her workstation should be analyzed and, if possible, delivered to him or her at the time it’s needed. This year, our focus has been to modify our process to a single order flow and to improve our staging of inbound orders to ultimately improve throughput by the optimal mix of finishes. Scheduling our extrusion orders to deliver the optimal mix for our anodizing operation was completed this year and has provided an increase in productivity as well as open capacity for our anodizing line.

Culture of Continuous Improvement

Continuous improvement is probably the most difficult step we’ve identified with lean manufacturing, and from what we have gleaned from other companies, we’re not alone. Continually auditing and driving continuous improvement will help maintain the momentum needed to develop a culture of continuous improvement and lean sustainment. Our company has developed a variety of tools to aid in this effort:

- Employee engagement. For example, each team member has a goal to submit 12 Waste Stoppers per year or one per month. This drives employee engagement and is the basis for small or larger kaizen improvements. It’s easy to measure, and great incentives are tied to meeting the goal.

- Standardized work. We developed a standardized checklist for leaders, managers and engineers to audit improvements and processes, and require that data and/or numbers be logged, rather just checked off as complete.

- Incentives. We offer creative incentives for performance, ideas and participation.

- New hires. The foundation of any culture is its people. Employee entrance into the culture is huge. Can temporary or staffing agencies select new employees better than you can? Doubtful!

- Culture of change. Employees need to be willing to embrace change, because the status quo is the opposite of continuous improvement. An open atmosphere of communication has to be present. If team members are afraid or can’t voice their opinions and concerns, growth is stifled and it’s difficult to improve.

- Measuring. If it can’t be measured, it’s not happening. If it’s not reported, it’s extremely difficult to change or improve.

There are many more tools not listed here that can help create a culture of continuous improvement. The list above has yielded great success for our company, and we believe it is the most valuable asset we have. It has provided the continual success we’ve realized as a company since the beginning of our lean journey.

Related Content

Chicago-Based Anodizer Doubles Capacity, Enhancing Technology

Chicago Anodizing Company recently completed a major renovation, increasing its capacity for hardcoat anodizing and Type II anodizing.

Read MoreFinishing Systems Provider Celebrates 150 Years, Looks to Future

From humble beginnings as an Indiana-based tin shop, Koch Finishing Systems has evolved into one of the most trusted finishing equipment providers in the industry.

Read MoreUnderstanding PEO Coatings

Using high-speed cameras and back side illumination (BSI) sensor technology to analyze plasma electrolytic oxidation.

Read MoreA Smooth Transition from One Anodizing Process to Another

Knowing when to switch from chromic acid anodizing to thin film sulfuric acid anodizing is important. Learn about why the change should be considered and the challenges in doing so.

Read MoreRead Next

Delivering Increased Benefits to Greenhouse Films

Baystar's Borstar technology is helping customers deliver better, more reliable production methods to greenhouse agriculture.

Read MoreA ‘Clean’ Agenda Offers Unique Presentations in Chicago

The 2024 Parts Cleaning Conference, co-located with the International Manufacturing Technology Show, includes presentations by several speakers who are new to the conference and topics that have not been covered in past editions of this event.

Read MoreEducation Bringing Cleaning to Machining

Debuting new speakers and cleaning technology content during this half-day workshop co-located with IMTS 2024.

Read More